Executive Summary

Youth mentoring programs, such as those of 4-H, Big Brothers Big Sisters and Boys and Girls Clubs of America, are an important strategy for supporting at-risk youth and preventing them from becoming entangled with the juvenile justice system. This white paper summarizes research showing that LGBTQ youth would benefit from access to these programs and makes recommendations for youth mentoring programs and local, state, and federal governments to ensure that access.

We estimate that there are 3.2 million LGBTQ youth (aged 8 to 18) in the United States. Approximately 61% are of these youth are girls and 39% are boys. In terms of race and ethnicity, 52% are youth of color—21% are Latino, 9% are Black, and 2.5% are Asian and Pacific Islander and 19.5% are multi-racial.

Following an analysis from a January 2014 report by MENTOR: The National Mentoring Project, we conservatively estimate that there are 1.6 million at-risk LGBTQ youth in the United States. More specifically, recent research indicates that:

- LGBT youth rank non-accepting families as the most important problem in their lives.

- Over 70% of LGBT youth feel unsafe at school because of their sexual orientation or gender expression.

- LGBT youth are almost twice as likely to consider dropping out of school as their non-LGBT peers.

- LGBTQ youth are at higher risk for drug use than non-LGBTQ youth.

- LGBT youth are much more likely be homeless or in foster care.

- LGB youth are over three times more likely to report that they have attempted suicide.

- While approximately 7% of youth generally identify as LGBTQ, almost 14% of youth in custody identify as LGBTQ.

Research shows that certain subpopulations of LGBTQ youth are more likely to face factors that put them at risk of involvement in the juvenile justice system than LGBTQ youth as a whole. These groups include LGBTQ youth of color, gender nonconforming youth and transgender youth.

This research indicates that LGBTQ youth are at risk for being, or are already entangled with, the juvenile justice system and would benefit from youth mentoring programs. As the 2014 MENTOR report concludes: “Research shows that certain populations are more likely than others to become at-risk –and therefore in greater need of the benefits that a quality mentoring relationship can provide. These groups include… youth that identifies as LGBTQ…Each of these populations has unique, and sometimes intersecting, challenges that mentoring can—and does—help address.”

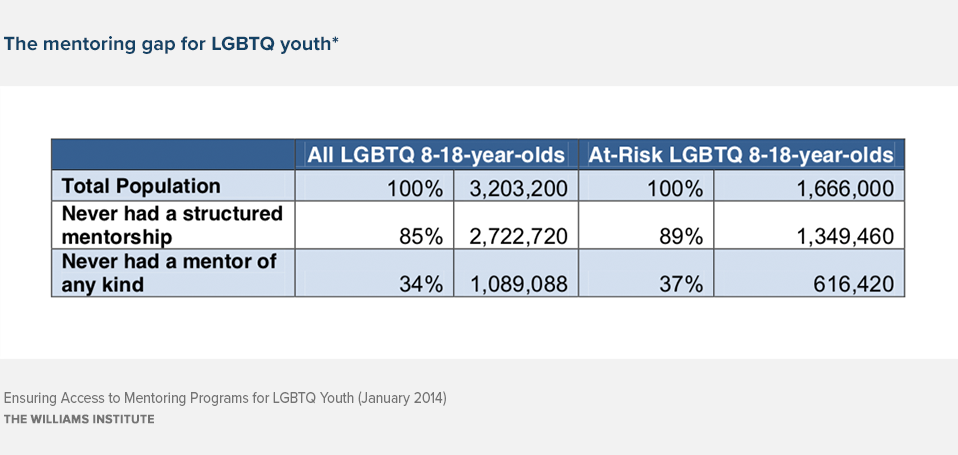

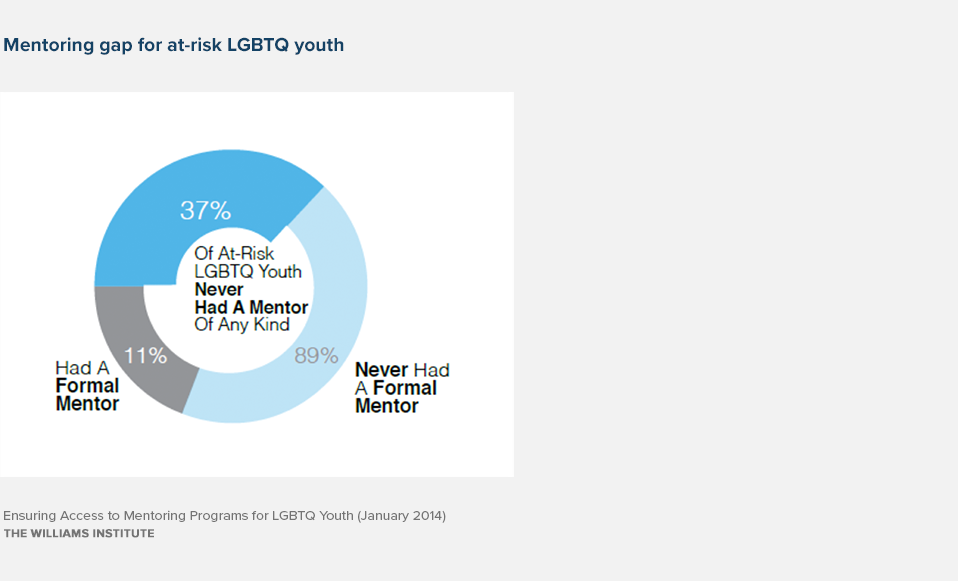

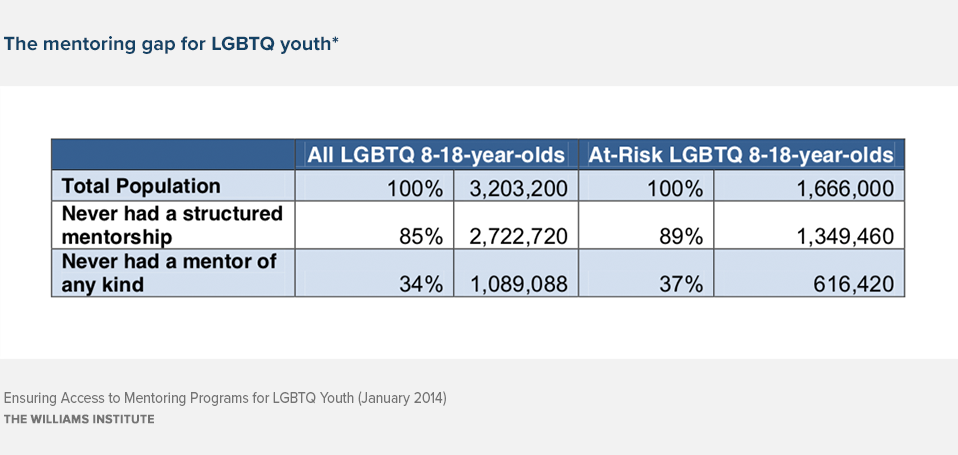

However, research also shows that LGBTQ youth currently face barriers to accessing youth mentoring programs and other social services. Following the 2014 MENTOR report analysis, we conservatively estimate that of the 3.2 million LGBTQ youth ages 8 to 18 in the United States, almost 1.l million have never had a mentor and under 500,000 have had a mentor through a formal or structured program. For the over 1.6 million at-risk LGBTQ youth, just over 600,000 have ever had a mentor, and fewer than one in five (just over 300,000) have had a formal mentor. In other words, we estimate that over 1.3 million at-risk LGBTQ youth have never had a formal mentor.

* Based on an analysis in Mary Bruce and John Bridgeland, The Mentoring Effect: Young People’s Perspectives on the Outcomes and Availability of Mentoring (Civic Enterprises with HART Research Associates for MENTOR: The National Mentoring Partnership, Jan. 2014), available at

http://www.mentoring.org/images/uploads/Report_TheMentoringEffect.pdf.

There is a need for policies and legal protections that ensure that LGBTQ youth have access to mentoring programs designed to reduce behaviors that can lead to involvement with the juvenile justice system. Key recommendations to ensure access to youth mentoring for LGBTQ youth include:

- Adopting internal policies and practices: Youth mentoring programs can adopt a number of policies and practices to ensure that their programs are accessible and welcoming to LGBTQ youth, as well as LGBTQ mentors. Such policies and practices include:

- Sexual orientation and gender identity non-discrimination and anti-harassment policies, and confidentiality policies;

- Inclusion of LGBTQ identity-affirming language on websites and other materials;

- Staff training focused on “best practices” for mentoring LGBTQ youth;

- Outreach practices targeting LGBTQ youth and LGBTQ-affirming mentors.

- Establishing LGBTQ-focused youth mentoring programs: Government and foundations can encourage the development of private programs for mentoring LGBTQ youth.

- Implementing LGBTQ-protective requirements in youth mentoring program grants: To further the objectives of youth mentoring programs, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention within the Department of Justice has the authority to issue guidance prohibiting grantees from discriminating based on sexual orientation and gender identity, to designate LGBTQ youth as an underserved population, and to specifically fund programs for LGBTQ youth.

- Enforcing existing legal protections: Several existing laws protect LGBTQ people to some extent, including Title VII, Title IX, constitutional provisions, and state nondiscrimination laws.

- Adopting new legal protections: Laws explicitly prohibiting sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination can be passed at the federal, state, and local levels.

In Part I of this paper, we provide an overview of youth mentoring programs. In Part II, we present the research demonstrating that LGBTQ youth need access to youth mentoring programs and would benefit from them. In Part III, we offer recommendations to ensure that LGBTQ youth have access to services through youth mentoring programs, including the availability of LGBTQ mentors.

Download the full report