Introduction and Summary

In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Windsor v. United States led to federal recognition of married same-sex couples in 2013. As a result, married same-sex couples gained additional incentives to marry: official recognition of their marriages by the federal government and some additional benefits and responsibilities of marriage that are rooted in federal law. Analyses of state administrative data suggest that the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision likely contributed to a marked increase in the number of same-sex couples marrying.

Key Findings

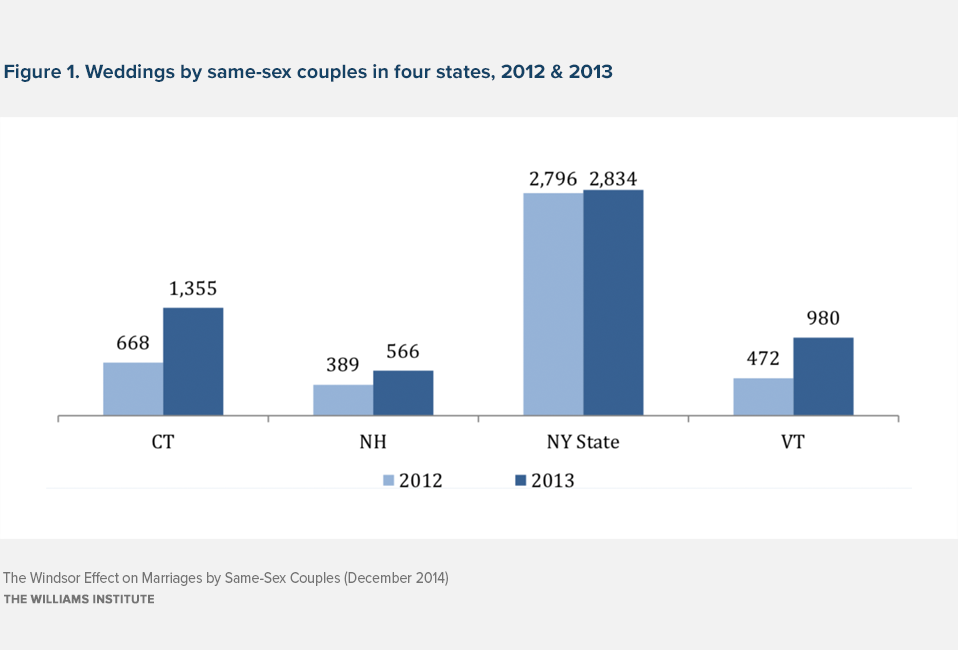

- Data from three New England states show that nearly twice as many couples married in 2013 than did in 2012.

- Monthly marriage counts from Connecticut show that 14% of all same-sex couples who have married in the state since 2008 did so in the six-month period following the Windsor decision.

- The higher number of marriages in 2013 reflects an increase both from couples in the states that provided data and from couples traveling to those states.

The Legal Impact of the Windsor Ruling

In the Windsor ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act, which prohibited the federal government from recognizing the marriages of same-sex couples. Since then, the federal government has gradually announced how that ruling would be implemented by federal agencies. Married same-sex couples who live in states that recognize their marriage have been afforded the same federal rights and benefits as married different-sex couples. If a same-sex couple marries in one state but resides in a state that does not recognize the marriage, the couple will be recognized for the purposes of most federal rights and benefits. However, in a non-recognition state, the couple may not be recognized for purposes of federal rights and benefits that are highly dependent on state law and administrative implementation, for example, state Medicaid programs.

The Impact of Windsor on the Number of Marriages

Both the expansion of legal benefits to same-sex couples and the symbolic power of federal recognition might have increased the economic and cultural incentives for same-sex couples to marry, boosting the number of same-sex couples beyond those who would have married without federal recognition. One way to assess whether this effect is present is to compare the number of marriages in 2013, or in the months after the Windsor decision, with the number of marriages that occurred in the same state in prior years or months.

In order to look for such a pattern in marriages over time, the Williams Institute collected administrative data on marriages in the 18 states that offered these statuses as of early 2014. All states were asked to provide a breakdown of the data by month and year. Four states were able to provide annual marriage data for 2013 and earlier years—Connecticut, New Hampshire, New York State (not including New York City), and Vermont. Connecticut and New York State (not including New York City) also provided a breakdown of marriage data by month.

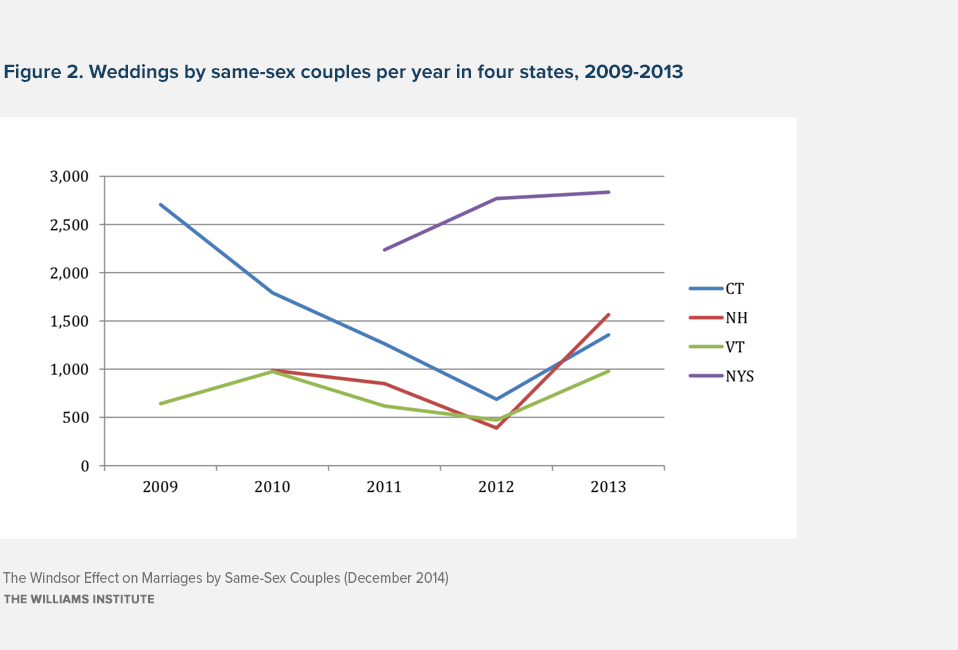

The marriage data show that before 2013, the number of weddings in Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Vermont decreased each year as the pent-up demand for weddings played itself out, as shown in Figure 2. In 2013, the number of weddings jumped in all three states, reversing that earlier downward trend and suggesting that the Windsor decision may have contributed to more marriages. The increase in marriages that occurred in 2013 was substantial. Across the three states, the number of same-sex couples who married nearly doubled from 2012 to 2013 (90% more couples married in 2013 than did in 2012).

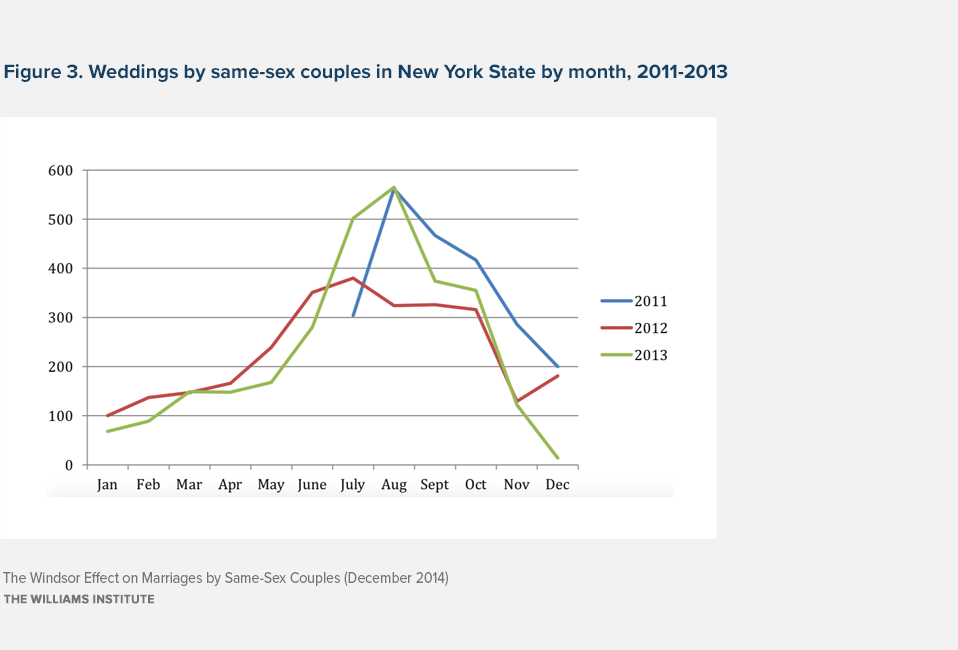

The New York State data follows a slightly different trend. This difference is likely because New York had more recently extended marriage to same-sex couples at the time the Windsor decision was issued than the other states. Past Williams Institute research has found that the demand for marriage is very high the first year it is offered and then drops substantially over the next few years. Given that New York extended marriage to same-sex couples in July 2011, we would expect to see the most marriages take place between July 2011 and July 2012 (see Figure 3 showing marriages by month). We would then expect to see the annual number of marriages decrease in each of the following years, as the data from the other states in Figure 2 indicate. However, the New York State data show that rather than decreasing, the number of marriages in New York State actually increased from 2012 to 2013 during the prime wedding months in the summer and early fall. This finding suggests that a Windsor effect was present in New York, but it was likely tempered by the substantial drops in demand that typically occur over the first few years.

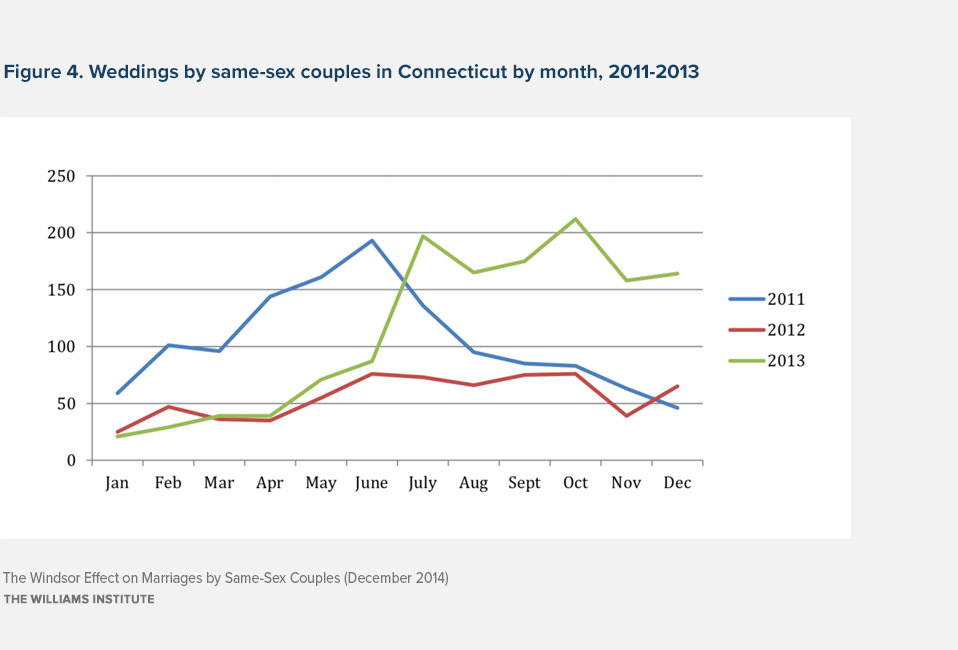

The post-Windsor pattern is even clearer in monthly data from Connecticut. Figure 4 presents the monthly weddings for 2011-2013. Both 2011 (blue line) and 2012 (red line) show the usual seasonal bump in weddings in the summer months, but by August 2011, weddings settled to under 100 per month. In contrast, in July 2013 weddings increased sharply to an average of 179 per month through the end of the year.

From November 2008, when marriage was extended to same-sex couples in Connecticut, through June 2013, 6,711 same-sex couples married in the state. In the second half of 2013, 1,071 same-sex couples married in Connecticut. This means that 14% of all same-sex couples who have married in Connecticut over five years married in the six-month period following the Windsor decision.

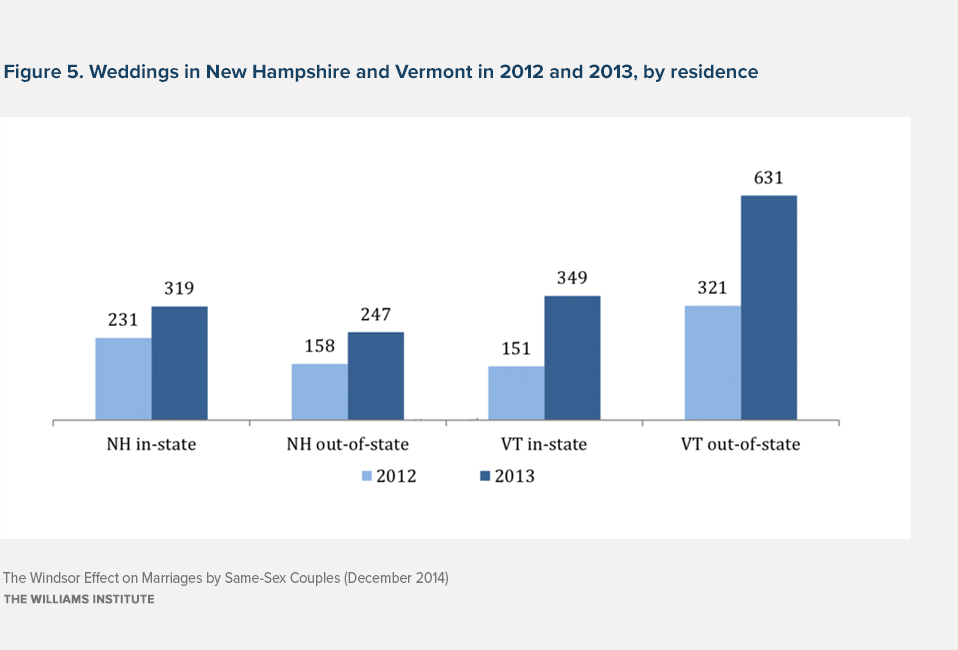

A final look at the post-Windsor data shows that the higher number of weddings in 2013 reflects an increase both from couples living in those states and from couples traveling to those states. New Hampshire and Vermont separate out weddings from in-state and out-of-state couples. Figure 5 shows that weddings increased for couples with at least one resident from the state as well as for couples coming from other states. The increase in 2013 over 2012 was particularly large for Vermont, roughly doubling the number of weddings for both in-state and out-of-state couples. Those states do not report whether the out-of-state couples come from states that do not allow same-sex couples to marry, but it seems likely that at least some of those marriages are not from marriage equality states.

Now that the marriages of same-sex couples have full equality at both the state and federal level (at least in those situations that involve federal recognition), same-sex couples’ decisions about marrying are likely to be different. Earlier Williams Institute research estimated that about half of all same-sex couples would marry within the first three years that marriage is available in a state based on marriage data prior to the Windsor decision. These new analyses suggest that future estimates should use a higher probability of marrying given the added benefits of federal marriage recognition. This analysis of data from the state agencies suggests that a Windsor effect was present in 2013 that substantially increased the likelihood of same-sex couples marrying after the Supreme Court’s Windsor decision.

Download the brief