President Trump has made access to public restrooms and other gendered facilities an early focal point of his administration. For example, on January 20, 2025, the president issued an executive order entitled “Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government,” which defines sex as only male and female, determined “at conception,” and unchangeable, for the purposes of federal programs, services, and spaces. Another executive order prohibits federally funded educational institutions from allowing minors to use restrooms that align with their gender identity if it differs from their anatomical sex. The president subsequently issued an executive order seeking to prevent the participation of transgender girls and women in federally funded girl’s and women’s sports and their use of women’s locker rooms.

In recent years, an increasing number of state legislatures have passed laws to require transgender people to use restrooms and other facilities in public buildings, such as schools and government buildings, according to their sex assigned at birth. Restroom access for transgender people has been the subject of policymaking in the U.S. House of Representatives regarding the use of U.S. House facilities. In November and December 2024, U.S. Rep. Nancy Mace filed two bills that would prohibit transgender people from using restrooms according to their gender identity on federal property (H.R. 10186, “Protecting Women’s Private Spaces Act”) and prohibit receipt of federal funds by any entity that allows transgender people to use restrooms and other gendered facilities according to their gender identity (H.R. 10290, “Stop the Invasion of Women’s Spaces Act”).

Those engaging in these efforts allege that new protections are needed for women’s safety and privacy in restrooms and other gendered facilities. For instance, the “Stop the Invasion of Women’s Spaces Act” and the transgender sports participation executive order (“Keeping Men Out of Women’s Sports”) are framed around the idea that the inclusion of transgender women in women’s spaces is inappropriate, unsafe, or violates privacy. The January 20 executive order specifically asserts that transgender women are a risk to “women’s safety” in “intimate single-sex spaces” and therefore, separation by anatomical sex in such spaces is necessary. In this brief, we review studies conducted by Williams Institute scholars that examine whether women’s restrooms and other gendered facilities pose added risk to occupants when transgender people are allowed to use those facilities according to their gender identity. We also review research on the experiences that transgender people report when using restrooms and the impact on transgender people’s lives when they cannot safely access restrooms.

Research on Overall Safety and Privacy in Public Restrooms and Other Gendered Facilities

Williams Institute scholars conducted studies in Massachusetts and nationally that assessed empirical evidence of impacts on safety and privacy in restrooms as a result of the enactment of nondiscrimination laws that protect transgender people’s ability to use restrooms according to their gender identity.

Study of Localities in Massachusetts

This study utilized data from criminal incident reports on safety and privacy violations related to assault, sex crimes, and voyeurism in public restrooms, locker rooms, and dressing rooms. Massachusetts localities with nondiscrimination laws that protect transgender people’s access to these facilities based on their gender identity were matched with localities without these protections. The matched pairs were compared over a period of time before and after the passage of the nondiscrimination laws. We found that:

- Incidents of safety and privacy violations in these spaces were rare.

- There was no significant change in privacy and safety violations across matched localities during the time period surrounding the enactment of nondiscrimination laws.

- There was no evidence that privacy and safety in restrooms changed as a result of transgender people having, by law, access to restrooms and other facilities in accordance with their gender identity.

Study of States and Counties across the United States

Building on the Massachusetts study, this study utilized data from the National Crime Victimization Survey to estimate the impact of gender identity nondiscrimination laws for public accommodations on the prevalence of violent victimization perpetrated by strangers. Violent victimization perpetrated by strangers is the type of crime that is purported to increase when transgender people may use restrooms and other gendered facilities according to their gender identity. We found that:

- When comparing states with and without these nondiscrimination laws, statewide implementation of these laws did not increase victimization rates perpetrated by strangers.

- When comparing counties with and without these nondiscrimination laws, neither statewide nor countywide implementation of these nondiscrimination laws resulted in increased victimization rates perpetrated by strangers.

- There was no evidence that violent victimization by strangers increased as a result of transgender people having, by law, access to restrooms that accord with their gender identity.

Research on Safety of Transgender People When Using Restrooms and Other Gendered Facilities

While we have found no evidence of increased harms to people who are not transgender when transgender people are allowed to use restrooms and other gendered facilities according to their gender identity, it is a consistent finding across studies and over time that transgender people report being denied access to these spaces and experiencing verbal harassment and physical assault from others in these spaces.

In a 2008 survey of transgender people in Washington, DC, 18% reported being denied access to a public restroom at least once in D.C. Sixty-eight percent (68%) reported ever being verbally harassed and 9% reported ever being physically assaulted in a D.C. public restroom.

- In the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, 9% of respondents reported being denied access to a restroom in the last year. Twelve percent (12%) reported being verbally harassed, physically attacked, or sexually assaulted when using a restroom in the last year.

- In the 2022 U.S. Transgender Survey, 4% of respondents reported being denied access to a restroom in a public place, at work, or at school in the last year. Six percent (6%) of respondents reported being verbally harassed, physically attacked, or experiencing unwanted sexual contact when accessing or using a restroom in the last year.

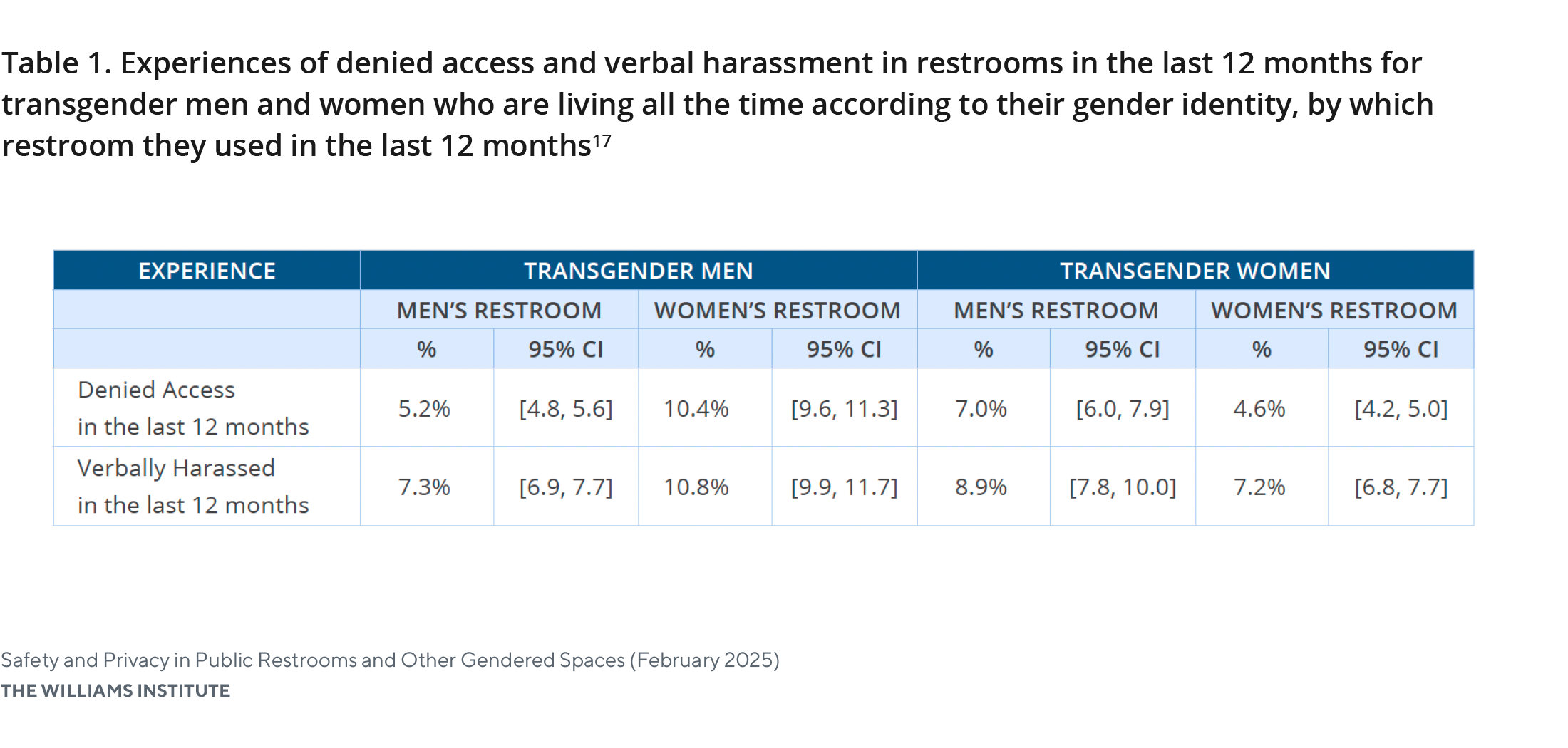

Analysis of data from the 2022 U.S. Transgender Survey suggests that negative incidents, such as being denied access when trying to use a restroom or verbal harassment when using a restroom, are more likely to occur when transgender people who are living their day-to-day lives according to their gender identity use the restroom of their sex assigned at birth. Transgender respondents who are living all the time according to their gender identity were significantly more likely to experience being denied access to a restroom or verbally harassed in a restroom when they used restrooms that matched their sex assigned at birth (See Table 1). For instance, nearly 11% of transgender men living all the time according to their gender identity and who used women’s restrooms regularly in the last year were verbally harassed in a restroom in the past year, compared to 7% of transgender men who used men’s restrooms regularly in the last year.