Levels of gender conformity are known to be a particular salient factor in the safety and well-being of youth. Yet, data about gender nonconforming (GNC) youth remain rare, particularly regarding the size, characteristics, and health of the population. In an effort to address this knowledge gap, representative data on gender expression were collected from California youth during the two-year 2015-2016 data cycle of the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS). This is the first representative survey of the adolescent population of California that included a measure of gender expression, which allows youth to be identified as GNC. In this fact sheet, we describe findings related to the demographics and mental health of GNC youth as compared to gender-conforming youth.

Characteristics and Mental Health of Gender Nonconforming Adolescents in California

Conducted in collaboration with the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, this study examines data collected from nearly 1,600 California households in the 2015-2016 California Health Interview Survey. This is the first representative survey of the state’s youth population to measure gender expression.

Defining Adolescent Gender Nonconformity

In the U.S., there are dominant cultural expectations about who gets to express masculinity and femininity, as well as about how best to do that. Although there are variations in how femininity and masculinity are defined and expressed both across cultural groups and over time, at the core of the dominant gender expression belief system is the expectation that people who are assigned female at birth should be “feminine,” and those assigned male at birth should be “masculine.” In essence, under these cultural expectations, individuals face social pressures to engage in gender-stereotypical appearance and behaviors in social situations and are sanctioned when they do not. California is one of several states that specifically prohibit discrimination against anyone who does not adhere to those stereotypes. People can defy gender stereotypes in terms of gender identity and/or gender expression, but these are distinct aspects of personal identity. Both transgender people (individuals for whom gender identity and assigned sex at birth are not fully concordant) and cisgender people (those for whom gender identity and assigned sex at birth are concordant) may be either nonconforming or conforming in their gender expression. People who are seen by others as gender nonconforming, along with those who are transgender or non-binary, fall under the umbrella of “gender minorities” – that is, people who are seen as resisting dominant expectations around gender expression and identity according to assigned sex at birth.

The California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) measured gender expression by asking every surveyed adolescent one question about how people at school viewed their physical expression of femininity and masculinity.

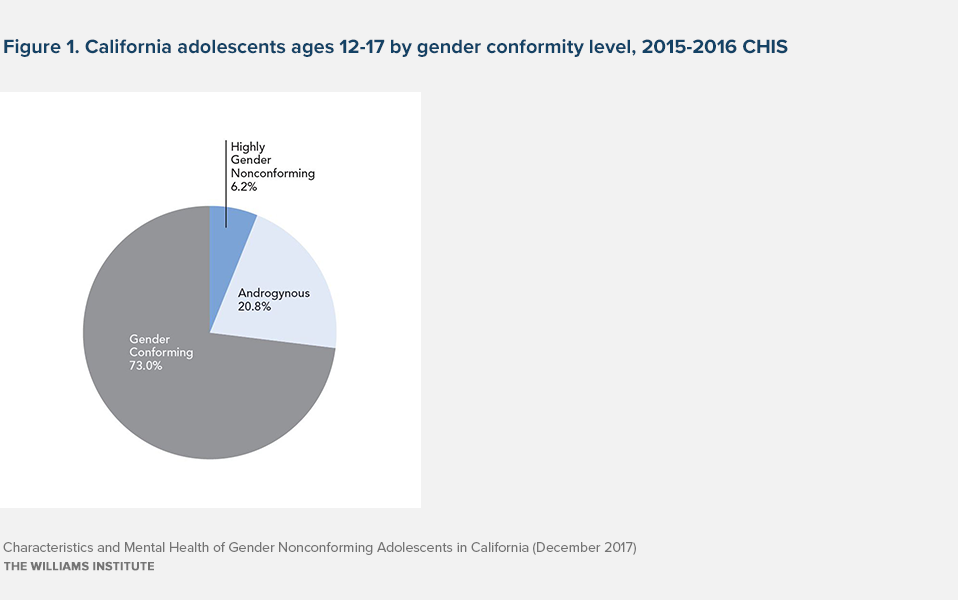

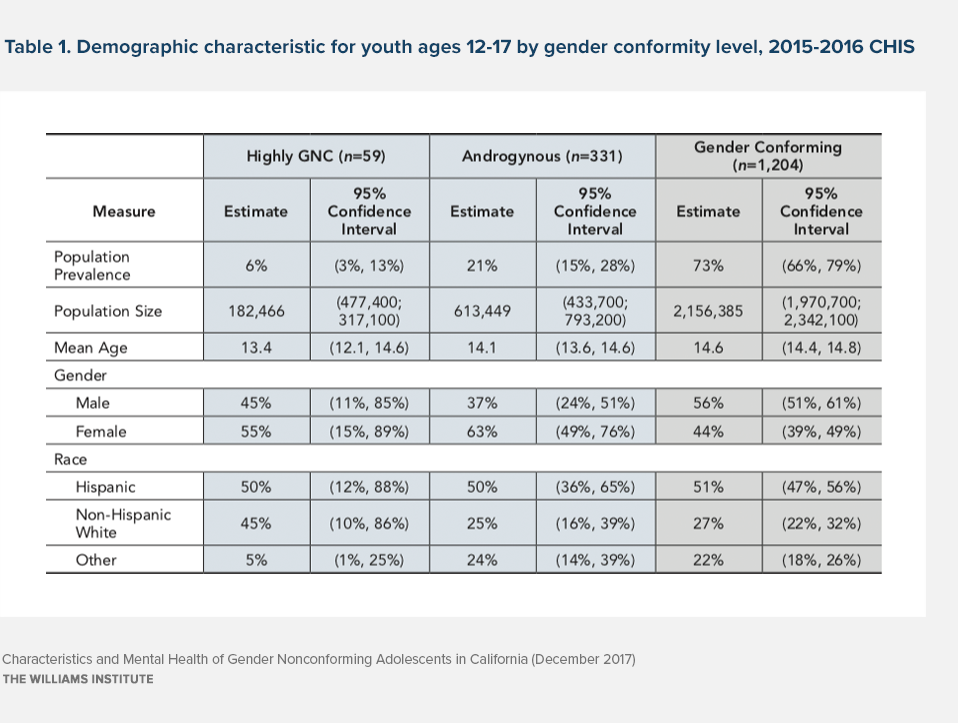

Responses to this item were then analyzed along with each adolescent’s response to the CHIS adolescent measure for sex/gender: “Are you male or female?” Based on these items, we identified two groups of GNC youth, “Highly GNC” and “Androgynous.” We categorized female youth as highly GNC if they responded with “mostly masculine” or “very masculine,” and we categorized male youth as highly GNC if they responded with “mostly feminine” or “very feminine.” We categorized GNC youth who reported being “equally feminine and masculine” as androgynous, and the remaining youth were categorized as gender-conforming (see Exhibit 1 for population percentages of each group and Exhibit 2 for demographic characteristics). We found that 27 percent of youth ages 12 to 17 in California, or about 796,000 youth, are GNC.

Mental Health

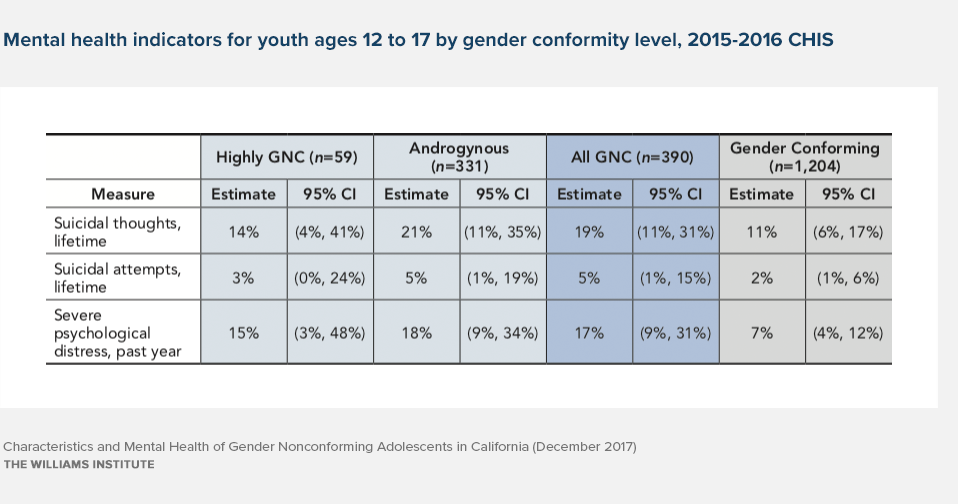

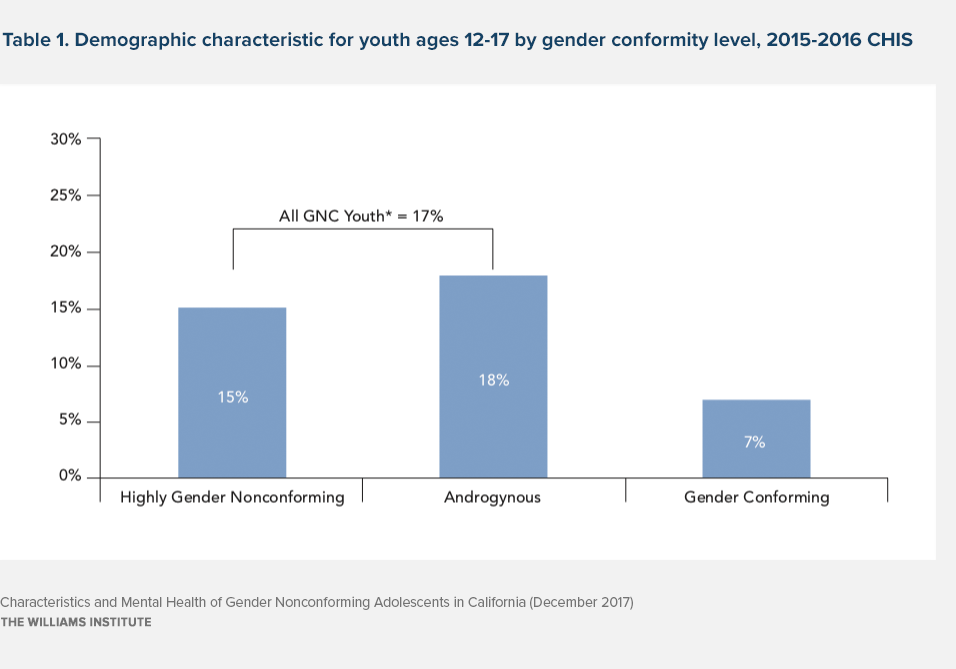

The CHIS adolescent questionnaire included several indicators of mental health, including psychological distress, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. GNC and gender-conforming youth did not statistically differ in their rates of lifetime suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts. However, GNC youth were significantly more likely to report severe psychological distress in the past year compared to gender-conforming youth (17 percent vs. 7 percent) (Exhibits 3 and 4).

Discussion

Gender nonconforming youth, including both highly GNC and androgynous subgroups, make up a significant segment of the adolescent population in California. GNC youth in our analyses did not have statistically significant higher levels of lifetime suicidality. This finding differs from an analysis of representative samples across several states and municipalities using a similar measure of gender expression, in which feminine males were found to have higher levels of suicide attempts than non-feminine males. Given that the estimates of suicidality among androgynous youth in this study were nearly twice that of gender-conforming youth, it is possible that a larger sample size will later reveal more precise confidence intervals and statistically significant differences.

It is also possible that higher levels of social acceptance and the presence of protective policies in California may impact rates of victimization and bullying, which, in turn, may confer some protection for gender minority youth in the state. Future studies should look at these data across several years and examine rates of victimization and bullying in order to better understand the relationships between laws and victimization and suicidality among GNC youth.

GNC youth were, however, more likely to be severely psychologically distressed compared to gender-conforming youth, a factor associated with future levels of suicidality. This finding highlights the need to increase access to affirming mental health care and other supports, as well as to educate parents, schools, and communities on the mental health needs of gender-nonconforming youth. It also makes it clear that we must focus on continuing to reduce known risk factors, such as bullying and bias, against gender-nonconforming people.

Methods Note

This report presents data from the new release of the 2015-2016 cycle of the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS), conducted by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research (CHPR). CHIS is a telephone survey that uses a dual-frame, random-digit-dial (RDD) technique. By using traditional landline RDD and cell-phone RDD sampling frames, it is representative of the state’s population. Survey items for the adolescent questionnaire are self-reported, and data are collected by trained interviewers. CHIS data are collected continuously throughout the year, with each full cycle comprising two years. Data are based on interviews conducted with adolescents in nearly 1,600 California households and covering a diverse array of health-related topics, including health status and behaviors and access to health care. For more information about CHIS, please visit the CHIS website at www.chis.ucla.edu.

All analyses presented in this fact sheet incorporate replicate weights to provide corrected confidence interval estimates and statistical tests. Differences in binary or categorical outcomes between gender nonconforming (GNC), androgynous, and gender-conforming respondents were tested using the Rao-Scott Chi-Square test, which accounts for the survey design’s use of replicate weights.

See, for instance: D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Starks MT. 2006. Childhood Gender Atypicality, Victimization, and PTSD Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 21: 1462-1482; Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM, Card NA, Russell ST. 2010. Gender Nonconforming Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth: School Victimization and Young Adult Psychosocial Adjustment. Developmental Psychology 46: 1580-1589; Gordon AR, Conron KJ, Calzo JP, White M, Reisner SL, Austin SB. Gender Expression, Violence, and Bullying Victimization: Findings from Probability Samples of High School Students in Four

U.S. School Districts. Journal of School Health (in press).

West C, Zimmerman DH. 1987. Doing Gender. Gender and Society 1(2): 125–151. http://www.jstor.org/stable/189945

Connell RW. 1995. Masculinities. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

California AB-887: http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/11-12/bill/asm/ab_0851-0900/ab_887_bill_20111009_chaptered.pdf

Kessler 6-Item Psychological Distress Scale (K6), ranges 0-24. We used a score of 13 or higher as a marker of severe psychological distress.

Gill AM, Frazer MS. 2016. Health Risk Behaviors Among Gender Expansive Students: Making the Case for Including a Measure of Gender Expression in Population-Based Surveys. Washington, D.C.: Advocates for Youth.