Introduction

HB 7111, Conscience Protection for Private Child-Placing Agencies, would allow all private agencies licensed to make foster care or adoption placement decisions in the state of Florida to do so in accordance with their own religious or moral convictions. The state would be prohibited from denying or revoking a license based on the failure to comply with rules if the agency cites a religious or moral objection to the rules.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals and same-sex couples could be among the potential foster or adoptive parents for whom placements would be refused under this proposed legislation. This memo provides estimates for the number of children being raised by lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals and same-sex couples in Florida, along with estimates of the potential fiscal implications if this bill causes children to stay longer in the foster care system rather than being placed for adoption.

Many LGB individuals and same-sex couples provide adoptive homes and foster care for children in the state, and LGB individuals are more willing than their non-LGB counterparts to consider adoption. If this legislation were to pass, LGB individuals and same-sex couples may find it more difficult to serve as adoptive or foster parents, resulting in more children remaining in foster care for longer periods of time.

The majority of child welfare and foster care resources in Florida go toward private community-based agencies. If these agencies refuse to place children for foster care or adoption with qualified individuals or couples based on religious or moral beliefs associated with objections to same-sex sexual orientations or coupling, fewer children in foster care may be adopted in the state. Foster care is generally more expensive to the state than adoption, and the state receives incentives from the federal government that increase with the number of adoptions from the foster care system. Reducing access to adoption services for LGB individuals and same-sex couples would result in higher state spending as more children who could otherwise be adopted remain in foster care.

Adoption and Fostering by LGB Adults and Same-sex Couples in Florida

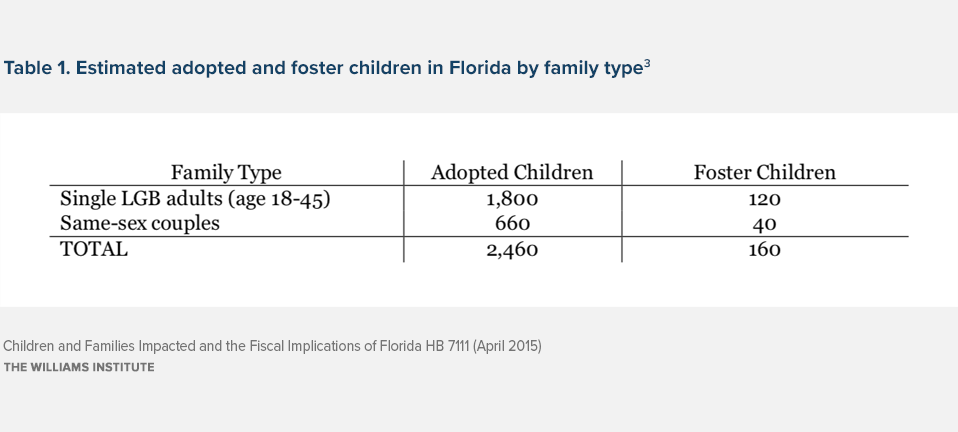

An estimated 2,460 adopted children under age 18 in Florida are being raised by LGB individuals and same-sex couples (see Table 1). Had HB 7111 been enacted before these children were being placed for adoption, these families could have been turned away by some agencies, and some of these children would have remained in foster care for a longer period of time awaiting adoption.

An estimated 160 foster children are living with LGB individuals or same-sex couples in Florida. These children have been placed in these homes because agencies have determined that they are the best placements for each child’s needs. It is possible that some of these foster parents may wish to adopt the children for whom they are providing foster care. Under HB 7111, private agencies with religious or moral objections associated with same-sex sexual orientations could deny children in such situations a permanent home through adoption by their foster families.

LGB individuals are much more open to the possibility of adopting than their non-LGB counterparts. Among women in the US aged 18-45 who say that they intend to have children or have more children, approximately 52% of LGB women say that they would consider adoption (unfortunately, a similar measure for men is not available). Among comparable non-LGB women, the figure is only 37%. Similar portions of LGB men and women in that age group (just over half) say that they intend to have children or more children if they already have them. If like their female counterparts, 52% of LGB men would consider adoption, then an estimated 53,000 LGB adults in Florida may be potential adoptive parents. These individuals may not be considered as adoptive or foster parents or may not pursue adoption or fostering as a result of agencies’ religious or moral objections to their sexual orientation or fear that such objections could be raised.

Fiscal Implications of HB 7111

The ability of adoption agencies to restrict services to LGB individuals or same-sex couples based on religious or moral objections potentially reduces the pool of adoptive homes in Florida and increases the chances that foster children will remain in foster care longer than necessary. For every child that remains in foster care rather than finding an adoptive home as a result of HB 7111, there will be negative fiscal implications for the state. States spend significant resources keeping children in foster care healthy and safe. These expenses include payments to foster parents for room and board, as much as $527.36 per month per child in Florida. They also include full Medicaid coverage for minors, as well as for young adults who have aged out of the foster care system but are younger than 26. Tuition and fee waivers at institutions in the Florida College System, state universities, and workforce education programs are also provided.

Studies find that children who are adopted have better physical, mental, and educational outcomes compared to children who remain in foster care. Permanency is an important goal for children. Adoption is also more cost-efficient for the state. A national analysis compared the costs to states of supporting foster children into adulthood. Comparisons are made between children who enter foster care and do not get adopted with those who are adopted from the foster care system. The average cost to the state of supporting children who enter foster care and are not adopted from the time they enter foster care until they turn age 18 was more than $135,000. If a child can be placed for adoption, the comparable cost was $67,000. On average, the study finds that a state saves approximately $68,000 over the course of a child’s life from birth to age 18 if the child can be placed with an adoptive family rather than keeping the child in foster care until adulthood.

Another study of adoption and fostering showed that, on average, the cost differential of placing a child for adoption versus keeping the child in foster care for a year is a nearly $15,500 savings. Estimates suggest that Florida bears about 41% of the costs associated with fostering children (the federal government pays the other 59%). If the estimated 160 children currently in foster care with single LGB adults and same-sex couples were to be adopted by them in the next year, the total savings could amount to nearly $2.5 million. This implies cost savings to the state of more than a million dollars that is put into jeopardy if LGB individuals and same-sex couples experience barriers to adopting foster children from private adoption agencies who object to providing services to them.

Creating barriers that limit the pool of prospective adoptive parents also has the potential to reduce adoption incentive payments that the federal government offers to states to encourage adoption. Since this program was first initiated in 1998, Florida has received more than $43 million. In 2013, the state received $3.5 million in adoption incentive payments. These incentives are put at risk when adoption becomes more difficult among the estimated 53,000 perspective LGB adoptive parents in the state.

Download the brief