Executive Summary

This study is the first to provide estimates of the percentage of sexual and gender minority adults experiencing homelessness compared to cisgender straight adults using representative national data. We provide estimates of homelessness (both recent experiences and lifetime prevalence) from three nationally representative surveys of U.S. adults conducted between 2016 and 2019 measuring sexual orientation and gender identity.

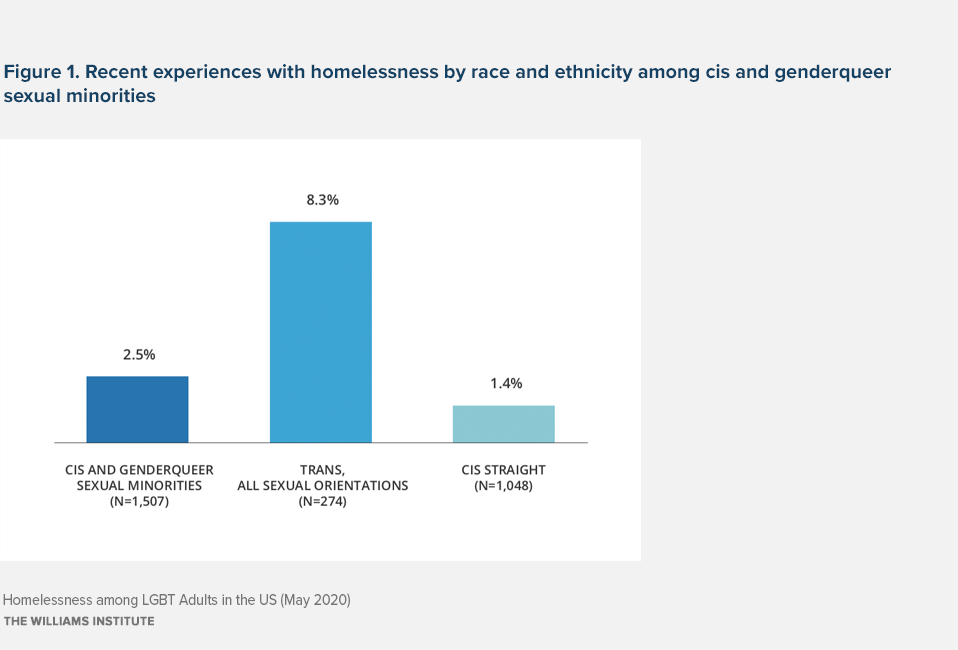

We examined the proportion of people who had recent experiences with homelessness (in the form of living temporarily with friends or family, living in a shelter or group home, or living in a place not intended for housing such as on the street, park, car, or abandoned building) in the 12 months prior to being surveyed. We found that:

- 8% of transgender adults across all sexual orientation identities;

- 3% of cisgender and genderqueer sexual minority adults;

- and 1% of cisgender straight adults reported indicators of recent homelessness.

- Among sexual minority adults, African American respondents had significantly higher rates (6%) of recent housing instability.

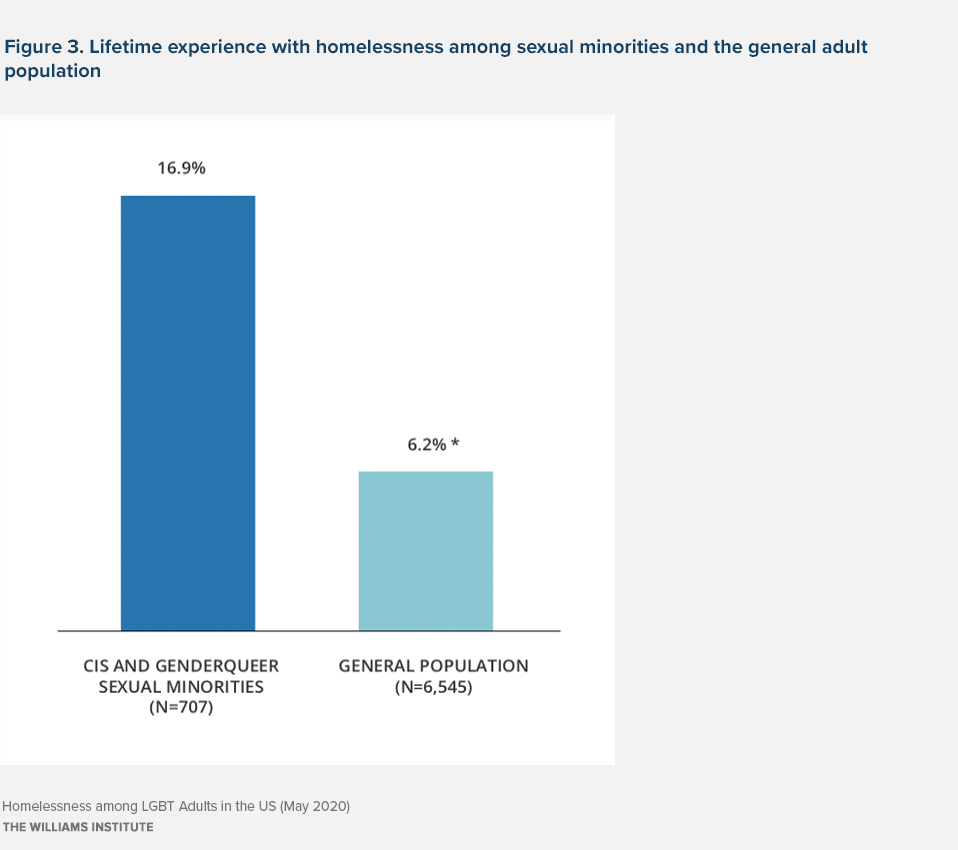

We also assessed the proportion of people who had experienced homelessness at any time in their life (measured only among cisgender and genderqueer sexual minority adults). We found that:

- 17% of sexual minority adults reported they experienced lifetime homelessness, which is more than twice what we have found in a general population study.

- Most respondents (71%) who had ever experienced homelessness did so as adults.

The study findings support concerns that homelessness is experienced at disproportional rates among sexual and gender minority people.

Overview

The assumption of overrepresentation of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people among those experiencing homelessness is widely discussed by policymakers and advocates, but very few studies have documented this using methods that reliably produce population estimates. Previous reports by the Williams Institute are often cited, but even these have been limited to reports of service providers surveyed using convenience sampling methods at the organizational level. Further, most work focused on this topic estimated youth homelessness and not the experience of homelessness throughout adulthood. We know that in California, approximately 25% of youth in schools who report forms of unstable housing are LGBT. Nationally, one study estimated that 22% of youth experiencing homelessness across 22 U.S. counties are LGB. Regarding adults, there are no nationally representative datasets of the population of people experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity that include measures of sexual orientation and gender identity.

Background

There is no singular definition of homelessness guiding a federal response to this problem. However, because even a single experience of being without permanent shelter can have negative impacts on health and economic stability, we adopt here the expanded view of homelessness in line with other researchers studying this issue among LGBT youth and adults, which includes multiple indicators of housing instability such as living on the streets, in shelters, and in other types of temporary situations (e.g., couch surfing, group homes). Other related terms for this social issue include “unstably housed” and “housing instability”; here, we use these interchangeably with “homelessness” as a way to represent an experience that people may have for various periods of time in their lives, and not as a demographic variable or personal characteristic.

Ideally, we would know how many adults who are unstably housed are LGBT because this would help us understand the relevance of sexual orientation and gender identity for those who currently need services.

However, another way to understand whether sexual orientation and gender identity matter in efforts to reduce homelessness is to examine whether sexual and gender minority people experience housing instability at different rates than cisgender heterosexual people. We provide data on homelessness (both recent experiences and lifetime prevalence) from three nationally representative surveys of U.S. adults measuring sexual orientation and gender identity. These three surveys conducted through the Generations Study and TransPop Study provide estimates of homelessness among transgender people (of all sexual orientations), sexual minorities (who are cisgender and genderqueer, but not transgender-identified), and cisgender heterosexual (straight) people. See the Methods Note for details regarding the studies from which the data were drawn.

Findings

Recent Experiences with Homelessness Among Sexual and Gender Minority Adults

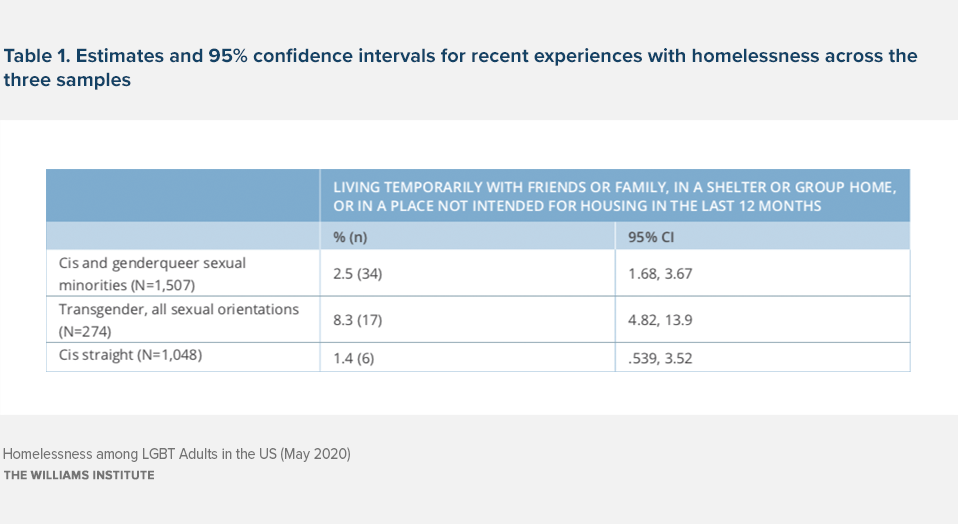

Approximately 8% of transgender adults of diverse sexual orientation identities (hereafter referred to as transgender for readability) reported recent experiences of homelessness in the 12 months prior to being interviewed in the form of living temporarily with friends or family, in a shelter or group home, or in a place not intended for housing such as on the street or in a car, park, or abandoned building. By contrast, 3% of cisgender and genderqueer sexual minority adults (hereafter referred to as sexual minorities for readability) and 1% of cisgender straight adults (hereafter referred to as cis straight for readability) reported recent experiences with homelessness (Figure 1). Looking at the confidence intervals from these separate samples, it appears that a significantly higher proportion of transgender people reported recent housing instability compared to both sexual minority and cis straight people (see Table 1).

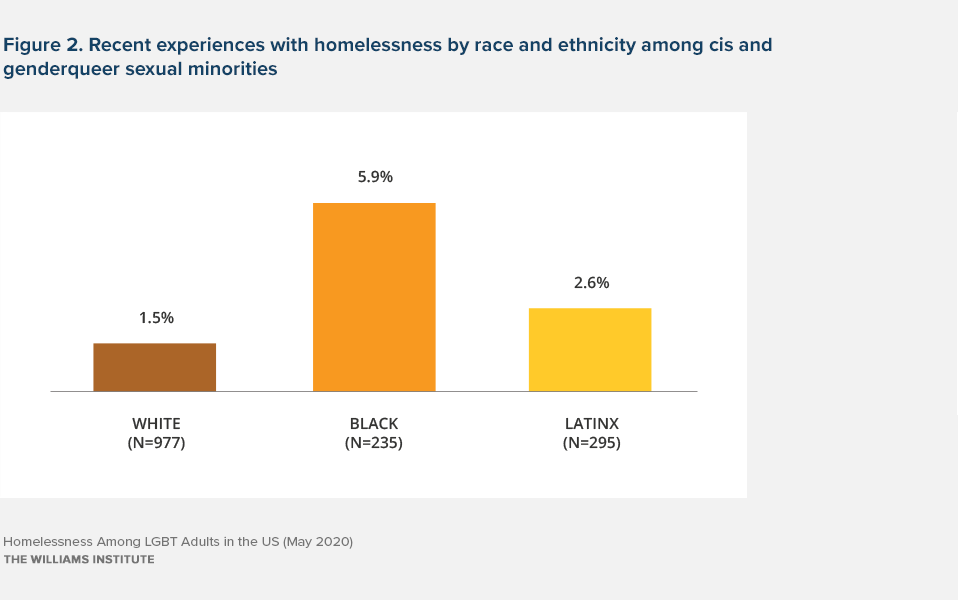

Racial and ethnic differences in recent experiences with homelessness among sexual minorities were significant, indicating disproportionately higher rates of recent experiences with homelessness among Black sexual minority people (Figure 2). Due to small sample sizes, we could not conduct statistical tests among subgroups of transgender and cis straight people (these values are provided in shaded text in Appendix A).

In addition to race and ethnicity, we examined differences by gender identity (trans woman, trans man, cis woman, cis man, and genderqueer/nonbinary), age groups (young adult, 18-25 years vs. older, 26 years or older), and gender expression (highly gender nonconforming vs. gender conforming) across all sexual orientation and gender identity groups. There were no significant differences (see Appendix A).

Lifetime Homelessness Among Cisgender and Genderqueer Sexual Minority Adults

We also assessed prevalence of lifetime homelessness in our population-based sample of sexual minority adults (this question was not asked in our surveys of transgender adults and cis straight people). Here, we find that 17% reported experiencing homelessness at some point in their lifetime, whereas the estimate of lifetime prevalence of homelessness in another study of the general population was approximately 6% (Figure 3).

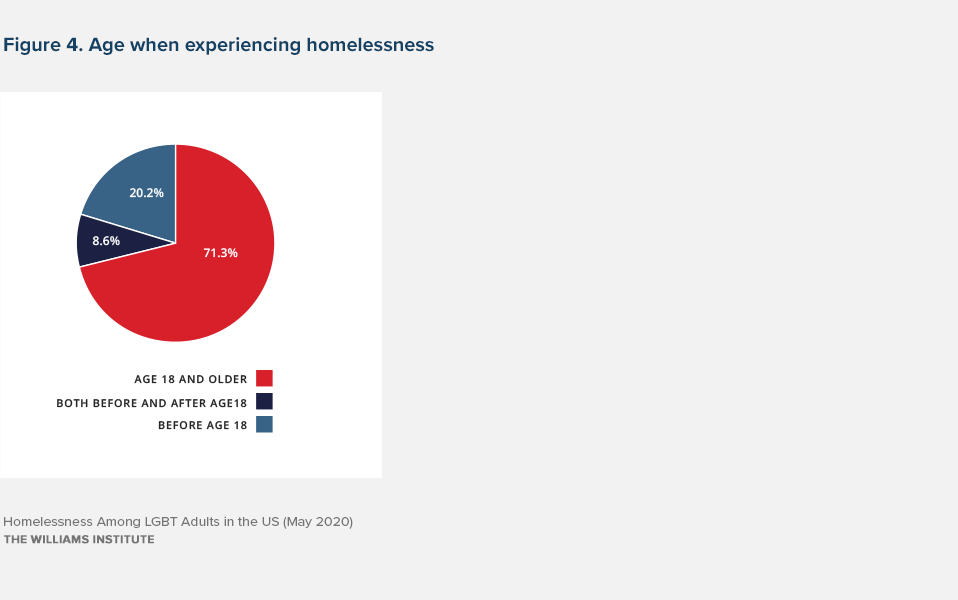

Among sexual minorities who experienced homelessness, the majority (71%) experienced it as an adult (age 18 years or older), 20% experienced homelessness before the age of 18, and 9% reported homelessness experiences in both youth and adulthood (Figure 4).

We examined whether there were any subgroup differences in experiences with lifetime homelessness in terms of race and ethnicity, gender identity, and level of gender conformity (See Appendix A for Tables with estimates and confidence intervals). Regarding the sexual minority sample by race and ethnicity, 23% of Latinx, 18% of Black or African American, and 15% of White sexual minorities reported having experienced homelessness, though these differences were not statistically significant.

Regarding gender identity among sexual minorities, 22% of genderqueer or nonbinary people, 17% of cis women, and 15% of cis men experienced homelessness. Additionally, 28% of sexual minorities who were highly gender nonconforming reported experiencing homelessness in their lifetime, whereas only 15% of those who were gender conforming had this experience. However, these differences were not statistically significant.

Implications

This study is the first to provide estimates of the proportion of sexual and gender minority people in the United States experiencing homelessness compared to cis straight people using a representative national sample. In this case, we have data for both recent and lifetime prevalence of homelessness among sexual minority people and only recent homelessness for transgender people. We see a significantly higher proportion of transgender people across sexual orientations reported recent housing instability compared to both cis and genderqueer sexual minority and cis straight people. Also, 17% of cis and genderqueer sexual minority people reported they experienced homelessness in their lifetime, which is more than twice that found in a study of the general population.

The reason for the lack of differences in rates of recent homelessness between cis and genderqueer sexual minorities and cis straight people is unclear, especially given the large differences in rates of lifetime homelessness. One possible explanation is that sexual minority people who are more economically secure may be more likely to volunteer for a survey than those who are not. Although we found that LGB people and other sexual minorities are more likely to experience unstable housing at some point in their life, the survey sample may be skewed toward people who are currently stably housed. It is plausible that unstably housed people have more difficulties maintaining a phone (which was our sampling frame) and thus were missed. Even if reached for sampling, it requires some form of stability to have a functioning phone, tablet, or computer and internet connectivity, or a mailing address, to respond to the self-administered online or mailed questionnaire.

Both subgroup differences and similarities in rates of homelessness point to important issues that could inform public policies and services. Among cis and genderqueer LGB people, African Americans had particularly high rates of recent experiences of homelessness. Although the sample sizes did not allow for racial and ethnic comparisons among transgender and cis straight people, the data suggest this may be a pattern across all groups. Given the high rates of poverty among people of color, whether LGBT or not, it is not surprising that we would also see high rates of recent housing insecurity. Knowing that homelessness historically has been experienced disproportionally by African Americans indicates a need to address housing instability among Black LGBT people in complex ways that are inclusive of, but not limited to, LGBT advocacy frameworks.

It is also notable that younger (18-25 years) and older (26+ years) adult sexual and gender minorities had similar rates of recent experiences with homelessness. However, in a previous study of youth in middle and high schools, scholars found higher rates of current housing instability than what we see in this study for young adults. Typically, research on youth homelessness focuses anywhere between ages 10-29 years, meaning it is often inclusive of young adulthood (also called emerging adulthood). Yet, there may be meaningful differences in rates of and experiences with housing instability among LGBT youth under 18 years compared to those that are young adults. These possible differences between age groups among LGBT youth requires further examination. Additionally, we found that most of the cis and genderqueer sexual minority respondents who had experienced homelessness at some point in their lifetime did so for the first time as adults. This emphasizes that although youth homelessness is an important issue among LGBT people, so is adult homelessness. Yet adult homelessness among sexual and gender minorities has received far less attention by advocates and public policy experts than youth homelessness. It is necessary to expand the scope of study and intervention of homelessness across the lifetime of LGBT people.

Download the full brief